During the Middle Ages (5th C to 15th C), a few major events happened in Highbury. We look at the first, a possible battle in Highbury Vale between Saxons & Vikings in 800, on the ‘Vikings at the Bottom of Our Gardens?’ page.

After 1066, with the invasion of William of Normandy, there was great change in the country. The new king gave land that became known as Highbury to one of his men, & the European feudal system was imposed on all living here. In 1381 the controversial Poll Tax sparked off the Peasants’ Revolt, with Highbury’s Lord of the Manor losing his head.

It is 5th January 1066 when Edward the Confessor, Saxon King of England, passes away. His successor, Harold Godwinson, is crowned King in Westminster Abbey the following day, 6th January 1066. Soon after the coronation King Harold marches north with his army to quell a Scandinavian invasion in York, leaving behind a militia of men & vessels to protect the south coast. The King is occupied in the north for months; the force guarding southern England remains in place till the end of August, when it disperses.

On 24th September King Harold & his army overwhelm Scandinavian forces at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. On 1st October, still recovering from battle, they learn that Duke William of Normandy has invaded England’s south coast. Harold & his army then march south until they meet William’s forces near Hastings on 14th October 1066. Saxons fight Normans from around 9am to dusk, but when King Harold is killed the battle ends. William of Normandy effectively becomes King of England, & English history is changed forever.

www.battle1066.com/normans.shtml

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hastings

William’s half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux & Earl of Kent, commissions a great tapestry to record the invasion. It is created in England & becomes known as the Bayeux Tapestry. It shows events leading up to the invasion – tree felling, shipbuilding, the appearance of Halley’s Comet in spring 1066 being explained to Harold by an astrologer – & it shows the battle itself, with Saxons v Normans.

For an animated view of the Battle of Hastings on the internet, tap into Bayeux filmpje at

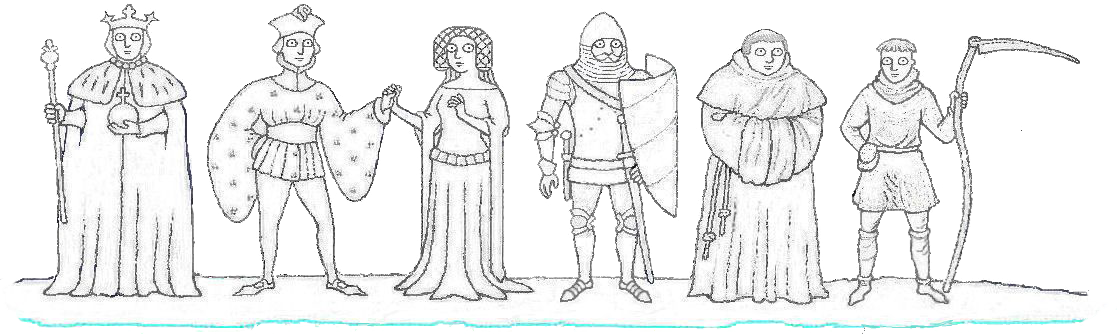

The new King & his followers set about imposing the European Feudal system on the Britons. Feudalism was a way of life in which everyone owed loyalty to one higher up: serfs, bound to the manor, owed loyalty to their lord. Knights owed loyalty to their lord. The church, & the lord, owed loyalty to the king, & the king owed loyalty to God.

“In much of feudal Europe, a land was organised into manors. At its simplest, a manor was made up of a big house, where a noble or knight lived, his home farm, called the demesne, and the surrounding fields, woods and pasture…”

25% of British land is allocated to the new king & 25% to the church. The remainder is divided among those who have been loyal to William, & others.

Everyday Life in the Middle Ages, Fiona Macdonald, Macdonald Educational 1984

People of the Middle Ages . http://www.themiddleages.net/people_middle_ages.html

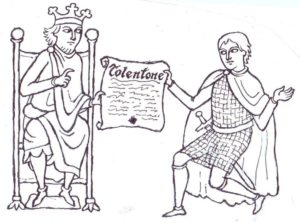

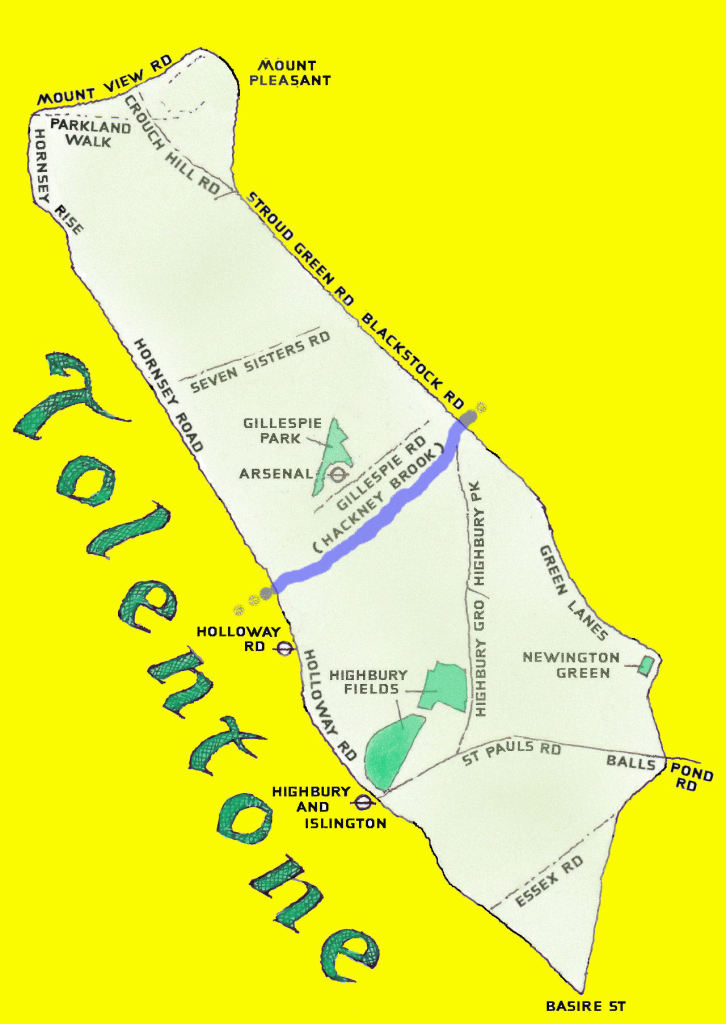

King William grants Highbury & the land surrounding it to Ranulf (Shield Wolf). The land, including Tolla’s Hill, an ancient right of way, becomes known as the Manor of Tolentone, with Ranulf the first Lord of the Manor.

Ranulf’s Tolentone, showing the position of the Hackney Brook, some of the main streets & the few green spaces that remain

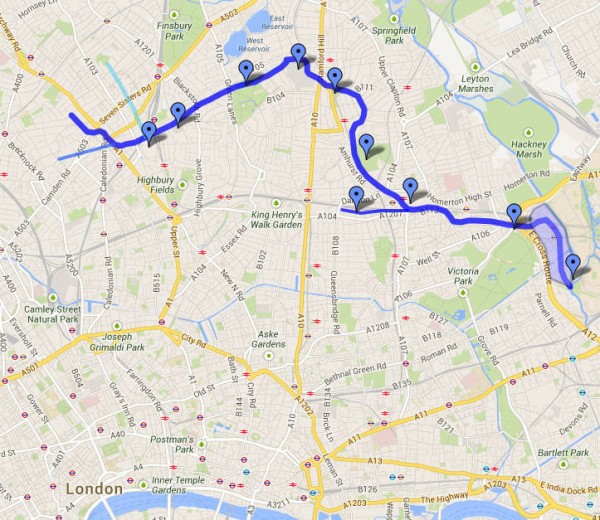

Tolentone Manor covers more land than today’s Highbury. It stretches from Vicarage Path on Crouch Hill/Mount Pleasant above Parkland Walk, down through Stroud Green, Highbury Hill & Newington Green to Ball’s Pond Road, & across Essex Road to Basire Street. Today’s Highbury & part of the Hackney Brook are within the Tolentone boundary.

Ranulf’s Land : Hackney Brook

Ranulf’s land is crossed by a river, the Hackney Brook. It flows west to east across what is now Highbury Vale, down present-day Isledon Rd along Gillespie Rd to Riversdale Rd. It crosses Clissold Park to Abney Park & flows on to the River Lea. ‘Hackney’ is from ‘Haca’s Ey’ – (Haca is Danish & Ey, an island)

Islington The First 2000 Years,

Pamela Shields

The Hackney Brook, flowing freely in Ranulf’s time, has been altered by human intervention. This tributary of the River Lea is now contained in an underground pipe.

In London’s Lost Rivers, Paul Talling looks at waterways that have been overwhelmed by the growth of London. The book has a Google map (left) which shows the Hackney Brook superimposed in blue over today’s road network.

The author conducts guided walks of London’s lost rivers, streams, canals, docks & wharves, much enjoyed by those who have gone on one. Tickets, limited to 20 per walk, usually sell out months in advance. See website for the guided walks mailing list.

London’s Lost Rivers by Paul Talling (ISBN: 9781847945976) http://www.londonslostrivers.com/authors-guided-walks.html info@ londonslostrivers.com

“The time estimate of walks is very rough as I’m in no hurry & these usually result in a social in the pub afterwards. These walks go ahead regardless of the weather – rain or shine, heatwave or arctic conditions! Please note that they are wholly above ground & there will be no subterranean trips down to the sewers! … I have public liability insurance. Well behaved dogs & children are welcome on all tours.” Paul Talling

Manor Court

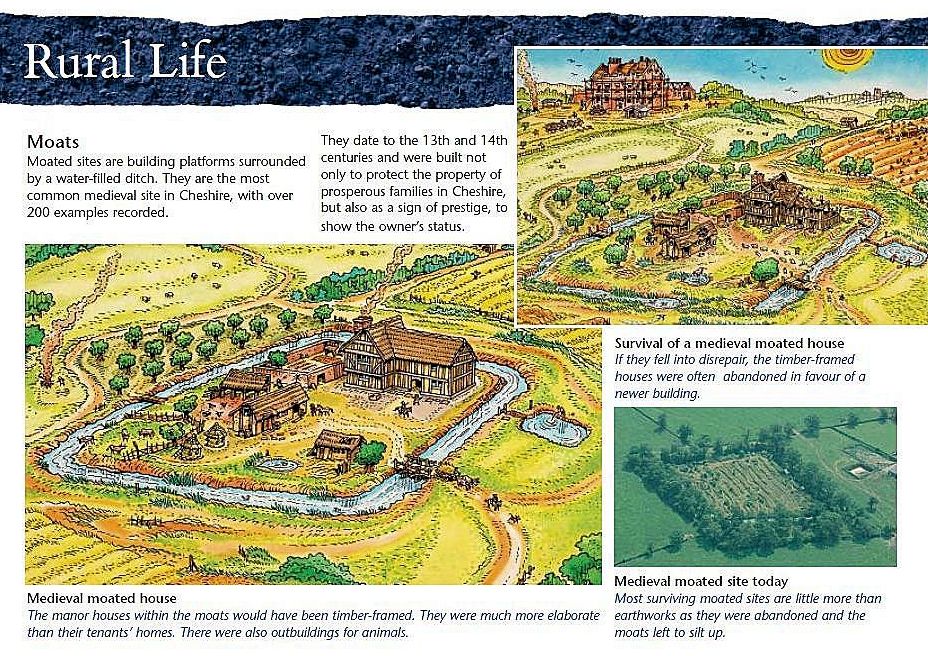

In the newly created Manor of a millenium ago, Ranulf builds his Manor House. It sits inside a moat on the east side of what is now Hornsey Road, at Tolentone’s northwest boundary. The new Lord of the Manor lives here, with his serfs, in Tolentone House.

The everyday work of feudal law takes place in the Manor House. Manor Court is held several times a year, either in Tolentone House or in the open air. Those not attending it are fined. Here, presided over by the Lord’s reeve or steward, decisions are made about taxes owed to the Lord, work not being properly done, the inheritance of land or the granting of permission to leave the Manor.

Over two hundred years go by, with feudalism now an intrinsic part of British society. In 1271 the Manor House of Tolentone & three hundred wooded acres are given by Lady Alicia de Barowe to the Knights of St John of Jerusalem (The Hospitallers), an extremely wealthy Benedictine priory based in Clerkenwell.

The Priory of St John is a self-contained community, with its own orchards and vineyards, a brewery & a distillery, livestock, an armoury, ships on the Fleet, & workers: millers, brewers, pharmacists, attorneys, clerks & others.

The Knights of St John look after travelers to the holy land, providing an escort from Clerkenwell to Jerusalem. The Hospitallers tend to their ailments & wounds, & the Knights Templar provide the military escort for their journey.

“The order was known as the Knights of St John, or the “Knights Hospitallers.” They took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The Pope recognized them as a new religious order and the Hospitallers were known for taking care of the “blessed sick poor.” The Clerkenwell Priory was a place of large-scale hospitality. The Order was above the nobility and answered directly to the Pope. Kings Henry VII and Henry VIII were called the “Protectors of the Order” and maintained a close relationship with the Hospitallers. The Priory also had power internationally and became a center for diplomacy and business.”

Clerkenwell Priory, Clerkenwell Medieval London Sites Medieval London

In 1300 a new manor house is built on the hilltop site of High Burh to replace Tolentone House. It becomes known as Highbury Manor, with Tolentone House now called The Lower Place.

This move, from one manor house to another, happened elsewhere in the Middle Ages. As a village grew in size around its manor house, with the public coming & going to Manor Court, the roads around it would have become steadily worse. Building a new Manor House some distance from the old one set it apart from the population it served. Surrounding it with a moat gave it even more gravitas, & nearby Barnesbury Manor, Canonbury Manor & Holloway Manor were all surrounded by moats.

Here the moat surrounds the property, rather than sitting against the building. This is more likely the sort of moat used for the Highbury Manor House and others in the area.

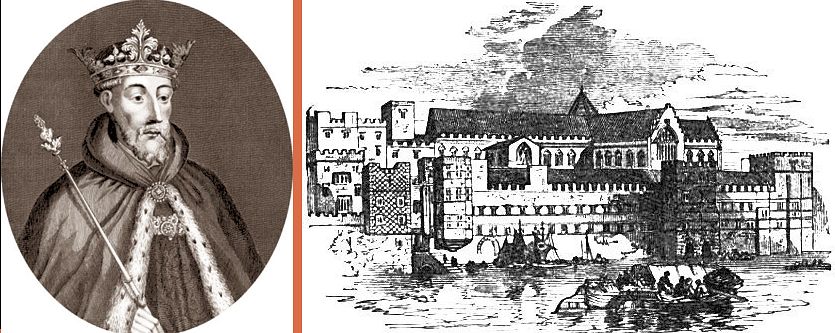

Sir Robert de Hales, 47, becomes Grand Prior of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, making him “…the third most influential man in England, second only to the king & the Archbishop of Canterbury. Prior Hales was not only an administrative dynamo, but also an active organiser of fleets & naval expeditions.”

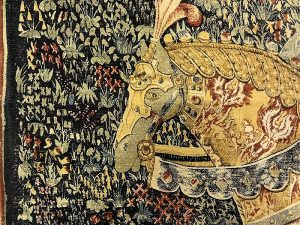

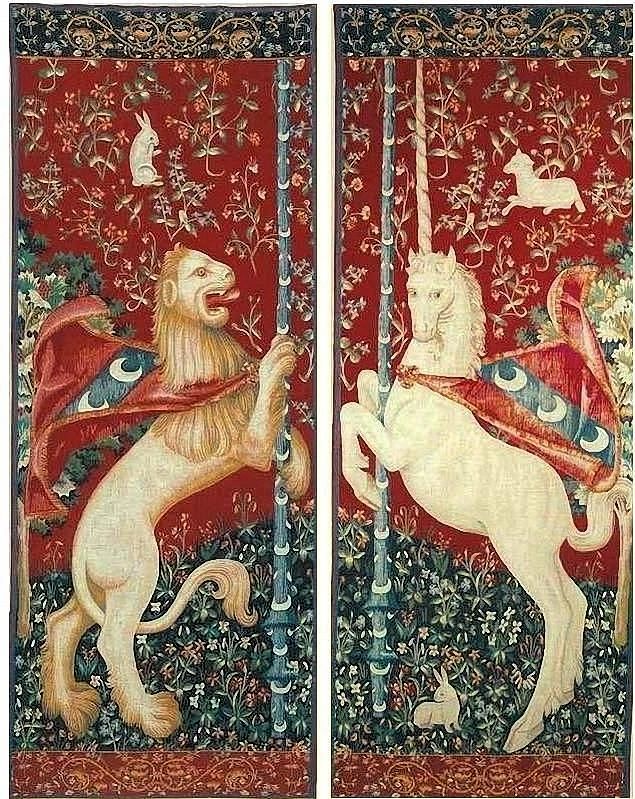

As the new Lord of Highbury Manor, Grand Prior Hales rebuilds its modest Manor House. The replacement is more grandiose than its predecessor. Canon John Milton of Leicester writes: “He constructed afresh the manor house of Highbury & made it as elegant as the alternative Paradise, as good as the Garden of Eden”. The Manor House may have been filled with tapestries, Greek sculptures, fine furniture & jewels from Prior Hales’ travels to the Middle East.

Keith Sugden, History of Highbury

There is a war on with France, the Hundred Years’ War. To pay for it, Parliament & the King levy a ‘hearth tax‘, the Poll Tax – a charge of fourpence (one groat) per person, to be paid by everyone in the country.

There is a war on with France, the Hundred Years’ War. To pay for it, Parliament & the King levy a ‘hearth tax‘, the Poll Tax – a charge of fourpence (one groat) per person, to be paid by everyone in the country.

Since 1300, the weather has worsened across the country & crops have failed. The Black Death has killed nearly half of the population. Those who remain, grieving for lost family & friends, must still find the money to pay the Poll Tax.

” Unlike previous poll taxes, where ability to pay had been taken into account, this one simply raised a flat rate of 1 shilling per person. As a result, evasion was widespread, with taxpayers concealing the existence of dependants such as widowed mothers or unmarried sisters. Eventually the poor rates of collection triggered a series of official investigations, held between January and March 1381. These had considerable success in uncovering deceptions, but they also created significant local unrest. ”

The National Archives / Exhibitions / Citizenship / Citizen or subject — Mozilla Firefox

Prior Hales’ ruthless tax collectors were diverting money to their own coffers: ‘The kyng therof had smalle’.

Lord Treasurer Prior de Hales, his tax collectors & their methods are all reviled. Canon John Milton of Leicester writes of Prior Hales: ‘he is among the most magnanimous and energetic of Knights but he does not please the community.’ (…’as we shall see...’Keith Sugden )

Medieval Lives, Terry Jones, 2004. BBC Documentary, Episode 1 – The Peasant

youtube terry jones medieval lives duckduckgohttps://duckduckgo.com/?q=youtube+terry+jones+medieval+lives&t=ffab&iax=videos&ia=videos&iai=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DQquhNTBfpdw

Medieval Lives, Terry Jones, 2004. BBC Documentary, Episode 2 – The Monk

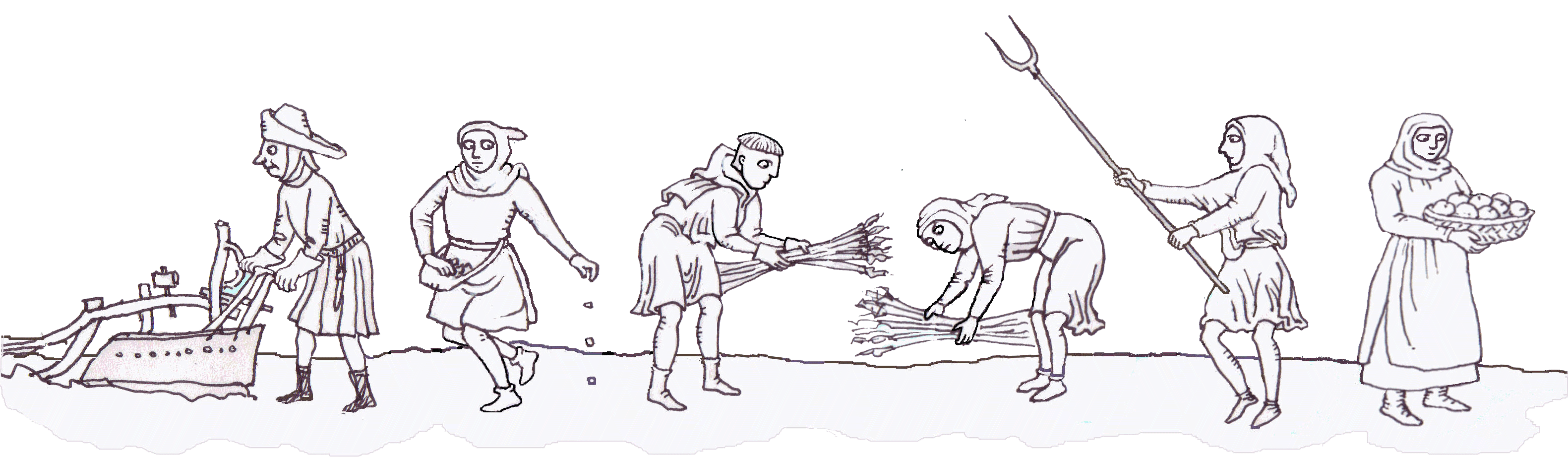

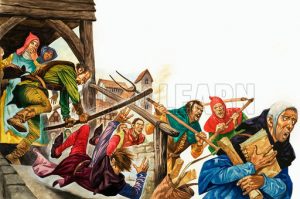

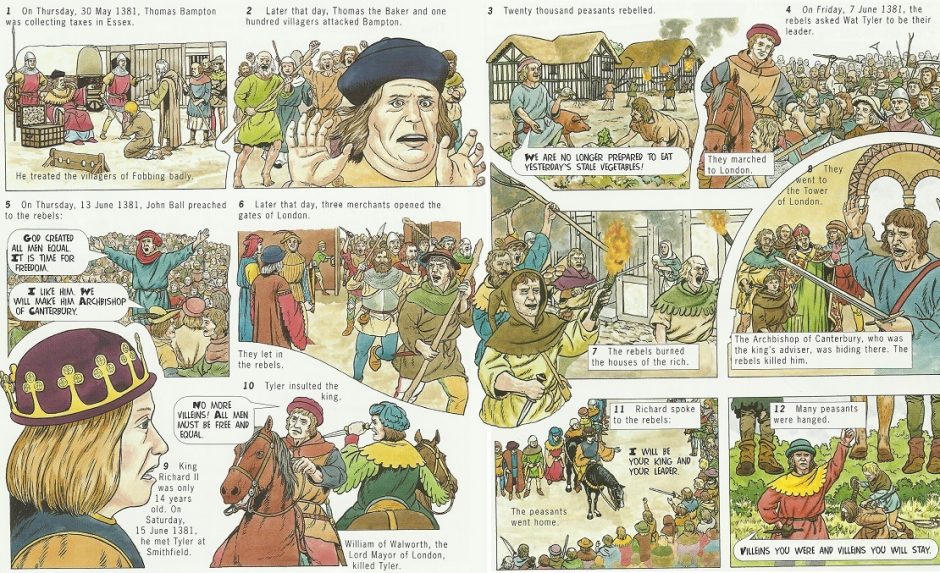

The peasants begin to act on their anger. Tax collectors are attacked, first in Essex, then in Kent. There is looting, arson & murder. Those who wish to protest about the Poll Tax gather for a march to London. Jack Straw leads the Essex protesters. On 7th June, Wat Tyler & his followers from Kent reach Canterbury. Joining the peasants are those who have legal problems with the poll tax – innkeepers, alewives, clergy & landowners.

They open Maidstone prison, freeing John Ball, the radical ‘peasants’ cleric’ imprisoned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, & march on to London, attracting others along the way. Well-to-do artisans & villeins join the peasants.

On 7th June John Ball preaches an open air sermon at Blackheath near Greenwich : “Our bondage or servitude came in by the unjust oppression of naughty men… Now the time is come … in which ye may (if ye will) cast off the yoke of bondage, and recover liberty.”

* www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/richint.htm – Literature of Richard II’s Reign and the Peasants’ Revolt: Introduction . Edited by James M. Dean . Orig. published in Medieval English Political Writings . Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 1996

On 13th June the rebels cross London Bridge & turn west, joined by Londoners. They set fire to John of Gaunt’s Savoy Palace & Fleet Prison.

Behind Thomas Farndon, they attack & sack the Priory of St John of Jerusalem (the Hospitallers) at Clerkenwell. The fire burns for days.

“…the Hospital itself was not disliked any more than any other

religious order; it was its prior who was thoroughly hated. While it was known

that Robert Hales was an active knight, he was not respected as a religious man

but regarded as a danger to ordinary people, the sort of knight who would

misuse armed power. His role as treasurer had given him a reputation for being

greedy and power–hungry.’

“Robert Hales could be regarded as acting less in his

order’s interests and more as an ambitious politician.”

Helen Nicholson, ‘The Hospitallers and the “Peasants’ Revolt”

of 1381 Revisited’ in The Military Orders. Volume 3. History and Heritage, ed. Victor Mallia-

Milanes. Copyright © 2007 Victor Mallia-Milanes. Ashgate Publishing Ltd,

Gower House, Croft Road, Aldershot, Hampshire, GU11 3HR, Great Britain, pp. 225–233.

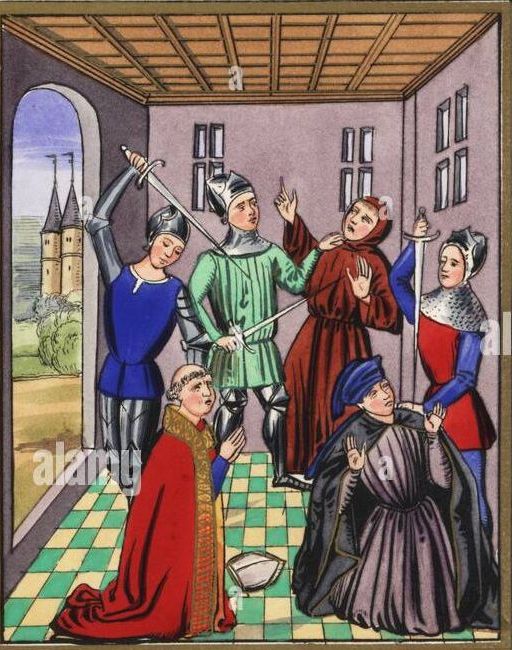

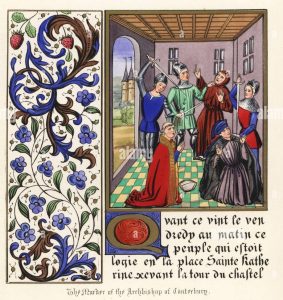

The Lord Treasurer of England, Grand Prior Sir Robert de Hales, takes refuge in the Tower of London with Archbishop of Canterbury Simon Sudbury, Chancellor of the Exchequer. After a day’s siege, the rebels finally break in; the Archbishop, the Grand Prior, John of Gaunt’s physician & John Legge, who had devised the Poll Tax, are all seized, dragged off to Tower Hill & beheaded. Their heads are stuck on pikes & carried in triumph around the city.

www.middle-ages.org.uk/the.peasants_revolt.htm Linda Alchin

—-

Coded messages

In this episode of Channel 4’s Timeline from 2004, author Mark O’Brien tells Tony Robinson of the coded messages carried in rebels’ pockets as they moved from village to village as a call to action. ‘Hobb the Robber’, the people’s nickname for the Grand Prior, singled him out for chastisement.

John Shep, sometime St Mary priest of York, and now in Colchester, greeteth well John Nameless and John Miller and John Carter and biddeth Piers Ploughman to go to his work and chastise well Hobb the Robber.

When Medieval Peasants Rioted Against the Crown / Peasants Revolt of 1381 / Timeline /Youtube / https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNu7YWay4E4

5eme SIA – The peasants’ revolt of 1381 – HG 2.0 bdidier fr.

5eme SIA – The peasants’ revolt of 1381 – HG 2.0 bdidier fr.

https://bdidier.fr/wp-content/uploads/PeasantsRevolt-2.jpg

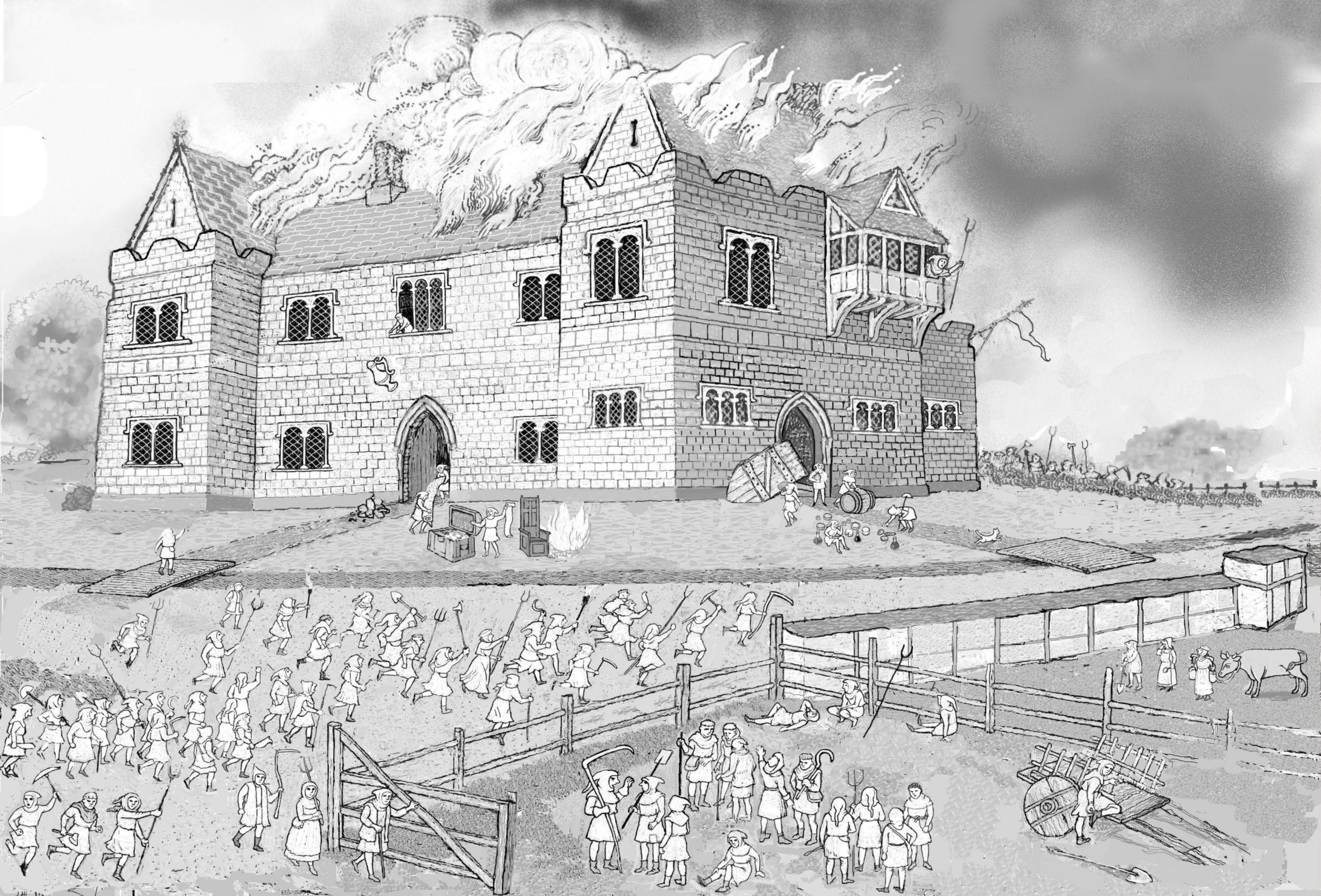

On the day following his death some of Prior Hales’ own servants (including one of his grooms) join 20,000 rebels on a march to Highbury Manor House; they sack & burn it. Robert Hales was Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitaller, whose ‘haughtiness, ambition and excessive riches’ offended the common people. *His association with the Poll Tax & the ruthless methods of his tax gatherers meant that he “provided something like a flashpoint for the mob’s fury”. Keith Sugden

This view of the Manor House as it might have looked is from across the road on the farm side of the property, the demesne. If you were a visitor, coming to the Manor by coach and horse, you would be traveling where most of the peasants are walking. Stables would be down the road to the right. After you had alighted & the Manor’s grooms taken charge of your horse(s), you would cross the road to enter the Manor by the front door. Inside is the great hall.

Inside the Manor House

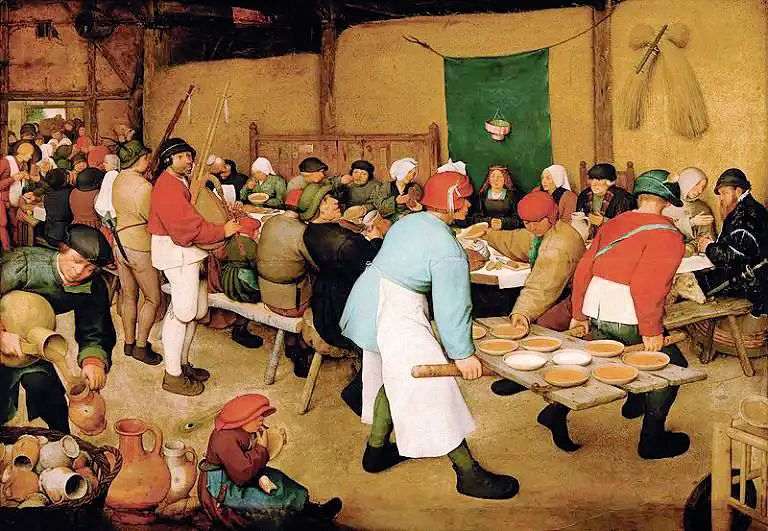

Inside the space would be dominated by a high vaulted beamed ceiling; a trestle table would have been set up for any meeting or meal. These tables were stored flat along the walls when not in use.

The floor would have been covered with strewing herbs – reeds, rushes and straw. These were used to mask unpleasant smells & provide pest control in the Middle Ages. Fragrant & astringent herbs were scattered – strewn – over the rushes straightaway, with more added over time. These herbs released a sweet smell when walked on, disguising any pongs that might have built up in the rush matting… crumbs of mouldering food, animal dander, mud etc. Certain herbs also acted as deterrents to snakes, rats, fleas & other pests.

‘Imagine the scene: you have traveled all day on foot or by horse. It is centuries before hotels, but you know you will be lodging with the local baron. You arrive at dusk, share a rowdy, highly seasoned meal in the torch-lit main hall, and get ready for sleep. The preparations are simple: the trestle eating tables are broken down and stacked against the walls. You elbow your way to a position near the central fire, make a pillow of your baggage, wrap yourself in your cloak, and stretch out on the hard floor, which is thickly strewn with rushes. You share the hall with all the other guests, much of the baron’s household and family, and the household dogs…’ Robbie Cranch, Mother Earth Living

https://www.motherearthliving.com/gardening/strewing-herbs-zmaz91djzgoe/

Serfs coming to Manor Court would also enter by the front door. Trestle tables would be set up for those attending. Presumably if there were more people than there were tables, latecomers would sit on the floor.

English trestle table, 16th C, wikipedia

English trestle table, 16th C, wikipedia

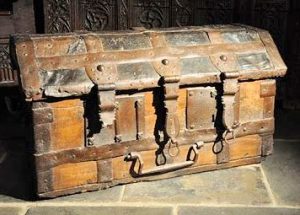

Lord Prior Robert de Hales or his reeve would be sat at one end, perhaps on a raised platform, with a scribe who wrote down details of each case – feudal details, personal details, poll tax details… These records were written on long rolls of paper, which would likely be kept in a chest under lock and key. In the picture the chest has been dragged out through the front door & the court rolls are being burnt.

Inside the Manor House

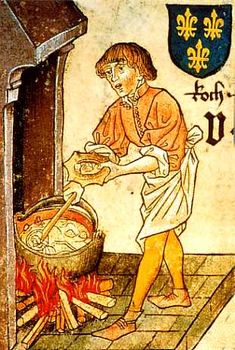

The side door opens into the kitchen, buttery & pantry. Servants for the Manor House, the cook & kitchen workers would use this side door.

Like other medieval kitchens of the nobility, Highbury Manor’s kitchen would have had an open fire, set inside a walk-in fireplace. Supplies for the kitchen would be brought over from the farm – grain threshed from wheat after harvest, bags of root vegetables, vine fruits etc, all carried or dragged across the little road, over the bridge that covered the moat & in through this side door, to be used straightaway or stored in the buttery or the pantry.

It could be that the Grand Prior employed two cooks. One, a grand cook for the Manor House, would have worked in the kitchens of the nobility & known about feasts, expensive imported spices, best meats, seafood & shellfish, imported wine & cheeses. When the Grand Prior was staying in the Manor House, (weekends?) this cook would have seen to it that he & his guests had only the best .

A Feast – King Richard ll dines with the Duke of York at John of Gaunt’s palace

A Feast – King Richard ll dines with the Duke of York at John of Gaunt’s palace

Even at the most elegant feasts, forks were not used until the 18th century. “Forks, however, never really caught on in Britain. Whilst our European cousins were tucking in with their new eating irons the British simply laughed at this ‘feminine affectation’ of the Italians, British men would eat with their fingers and were proud! What’s more, even the church was against the use of forks (despite them being in the Bible)! Some writers for the Roman Catholic Church declared it an excessive delicacy, God in his wisdom had provided us with natural forks, in our fingers, and it would be an insult to him to substitute them for these metallic devices. “

Leah, Customer Service Library Attendant, History of the Fork, Royal Maritime Museum, Royal Museums, Greenwich, 2007.

There would have been a cook for the Manor’s farmworkers. The cuisine was simpler here, with pottage the main meal, a cauldron of peas, beans and onions in a vegetable stew with the occasional morsel of meat… seasoned with local herbs & spices, to be eaten with ‘trenchers’ of day old rye bread.

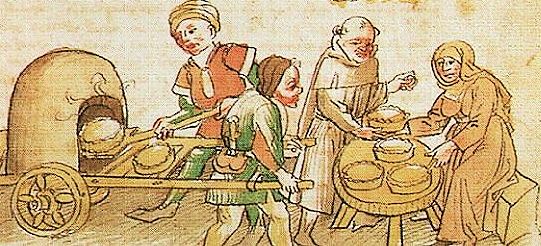

Baking was a fire risk to kitchens in medieval times, so in many places baking facilities were located outside the city walls. Some baking was done in portable ovens on wheels, with bread or pies moved in & out of the oven on long paddles. It could be that this sort of oven was wheeled about on the farm side, while the Manor House kitchen had a more permanent stone oven built on a stone base.

The preferred bread for the nobility was white bread made from wheat grain. The poor ate rough bread made from rye, oats, and barley. ‘Biscuits were created in the Middle Ages by baking bread twice. ‘which left it crispy, flaky and easy to preserve. They were considered ideal for long travels, war and for storing them for winter months.’

For more detail on medieval bakers, go here:

https://medievalbritain.com/type/medieval-life/occupations/medieval-baker/”

In Highbury Manor, a circular stone staircase would have led from the corner of the kitchen area up to Prior Hales’ quarters. Breakfast for him & any guests could have been carried up these stairs by kitchen staff or be set out on the downstairs trestle tables, whichever he chose. A servant would have pulled back the curtains from the windows, perhaps striking a gong brought from abroad by Robert Hales, calling out ‘breakfast is on the table, Lord Prior’…

Breakfast would have been leftovers from the night before, set out on trays – No coffee (not until the mid-1600s) or tea (not until the early 1700s), so probably wine or ale to drink.

Inside the Manor House

The Priory at Clerkenwell was Robert Hales’ primary residence; this Manor House at Highbury was ‘a country retreat’ for the priors. Its rebuilding was down to his own design. He could have planned the best situation for his work upstairs at a central trestle table, catching the east light through the windows in the morning, and the west light towards dusk From the other windows he could look over Highbury Farm and watch for the arrival of any guests.

Canon John Milton of Leicester writes that The Grand Prior had made this Manor House ‘as good as the alternate Garden of Eden’… On the ground floor, kitchen, buttery & pantry were all about food preparation & storage… the grand hall would have been left open for visitors to Manor Court. So Robert Hale’s fine things – tapestries, draperies, carpets, artefacts – would most likely have been set out on the upper floor.

A building of stone can be penetratingly cold, more so in Britain than in some of the hotter countries to which Robert Hales had traveled. Tapestries would have served a more than decorative purpose – they would have added an element of warmth to the building. As would any Middle Eastern carpets or rugs he may have brought back with him. These may have been set out on the floor upstairs, rather than the rushes & strewing herbs laid out in the great hall below.

Robert Hales might have spent much time pacing the floor around a central trestle table, looking out of the windows, making his plans.

That week, while working out strategies for the ongoing war against France, The Grand Prior might have said to the Archbishop of Canterbury,

Chancellor of the Exchequer and Archbishop of Canterbury Simon Sudbury with Grand Prior and Treasurer Robert Hales / Timeline / Channel 4 Television / 2004

‘Perhaps you might come to Highbury for the weekend, my Lord Archbishop, for some country air & slight diversion from our work here. Cook will arrange a small feast for us, with oysters, river fish, venison, wild boar, watermelon, strawberries & cream from my own cows.’ The Archbishop might have agreed.

So imagine the Highbury staff being told that the special guest staying at the Manor that weekend would be the Archbishop of Canterbury, Chancellor of the Exchequer … Robert Hale’s colleague at planning the war with France for which everyone would be paying the poll tax… Then came the 13th of June, the Peasants’ Revolt, & suddenly both had been beheaded & everything had changed.

After sacking and burning the Grand Prior’s residence at Clerkenwell Priory, seizing & beheading Prior Hales & the Archbishop of Canterbury on the previous day, 20,000 of the rebels (including some women) now trudge from Clerkenwell to Highbury. This is a sizeable walk, mostly uphill. Rebels would have already journeyed some distance from their villages, from Kent, Essex…

Peasants Revolt The time when women took up arms BBC Melissa Hogenboom https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18373149

If you have been on guided walks or demonstrations you may recall someone not so fit as the others falling behind, struggling to keep up. In The London Marathon of today, it is the St John Ambulance who support the runners. In this picture the rebels to the left have walked a marathon and are fading, perhaps having witnessed beheadings & fires, just trudging now to keep up. People using canes wanted to be here, on this historic occasion.

Some rebels now congregate in a nearby field & watch the Manor House burn. The sight of it in flames revitalizes others & they break into a run. Agricultural implements on display include billhooks, scythes and pitchforks.

On the farm opposite the Manor House there would have been stables, barns, sleeping quarters for the workers, orchards, vineyards, beehives, storage for fruit, vegetables & grain, & various outbuildings, aside from the fields where crops were grown.

Below right is an example of grain storage from Midhurst, West Sussex. The building rests on staddle stones, granite mushroom-shaped supports which deter mice. Workers enter and leave the building by a ladder to the door. Such a building could have been on the farm as a mouse deterrent.

Researching the History of the Barn : https://www.buildinghistory.org/buildings/barns.shtml

It is not known what food and drink would have been found in the Manor’s kitchen pantry, so this is guesswork. In the picture, rebels are leaving the kitchen area with pies, cheeses, bread & oak barrels of wine & ale. There was no refrigeration at this time. Pies & cheeses could have lasted for some time, stored in stone enclosures, topped with a piece of slate to keep mice out. Bread is likely to have been baked that day. Imported drink, as there was a war on with France, probably came from Portugal or Spain.

Medieval Chronicles – Medieval Food Recipes – https://www.medievalchronicles.com/medieval-food/medieval-recipes/

MedievalMadness . What Was the Diet of a Medieval Peasant . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H21Olb24cpY

The Romans had introduced ‘asparagus, turnips, peas, garlic, cabbages, celery, onions, leeks, cucumbers, globe artichokes, figs, medlars, sweet chestnuts, cherries and plums’ as well as the grape, introducing the wine industry to Britain. “Before the fourteenth century western Europe’s climate was much warmer than it is now and wine could be grown successfully in England”. Medieval Monastic Garden, Sara Douglass Enterprises Pty Ltd, 2006.

Herbs and spices such as mint, coriander, rosemary, radish & garlic were introduced & cultivated. Rabbits, chicken & shellfish were to be found on the tables of the elite, with oysters much favoured. Roman Food in Britain, Historic UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryofBritain/Roman-Food-in-Britain/

A 14th C recipe printed by Geoffrey Chaucer for Apple Pie contained no sugar, but plenty of other ingredients, such as figs, raisins and pears. A Shortcrust History of Pies, BBC Bitesize

In the picture we have given the cook an official mouser, a cat who stands guard over kitchen, buttery & pantry, keeping the area free of rodents. Noisy rebels have broken in through the kitchen door and the cat now races over the moat and across the road to the farm.

Nun spinning thread as her pet cat plays with the spindle, Maastricht Hours, the Netherlands (Liege), 1st quarter of the 14th C, Stowe MS.

Cats in the Middle Ages

Cats were first brought to Britain by the Romans, & their fortunes fluctuated over the centuries. In the Middle Ages, black cats especially suffered from a believed link to witches & the devil, & were often culled because of this. But the undeniable gifts of the cat at mouse-catching meant many were gainfully employed by humans for protection of food supplies. Free board and all the rodents they could eat. For a time cats were the only pets allowed as companions to monks and nuns.

Pangur Ban

An Irish monk, fleeing the Vikings in the 8th Century, becomes a student at the Benedictine Monastery of Carinthia in Wolfsburg, Austria. He writes a poem in Gaelic and English to his cat companion, Pangur Ban. The poem, written on a copy of St Paul’s Epistles, has been translated by Robin Flower. http://www.sky-net.org.uk/canals/pangurban/name/

The Exeter Cathedral Cat Flap

“A cat was paid a penny a week in the 15th century, to keep down the rats and mice in the north tower, and a cat flap was cut into the door below the astronomical clock to allow the cat to carry out its duties.Records of payments were entered in the Cathedral archives from 1305 to 1467, the penny a week being enough to buy food to supplement a heavy diet of rodents.”

The Peasants’ Revolt spreads to other parts of the country; St Albans, Bury St Edmunds, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire. It eventually ends with its leaders executed. Wat Tyler is killed at Smithfield, at a meeting between the 14-year old King Richard II and the rebels; his head is removed, stuck on a pike & displayed on London Bridge. John Ball is tried, hung, drawn & quartered & his head stuck on a pike on London Bridge.

—————————————————————————————————————————

Your Guide to the Peasants Revolt of 1381 – History Extra, The official website for BBC History Magazine and BBC History Revealed

Helen Carr, Historian and Author

https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/your-guide-peasants-revolt-facts-timeline/

For over 300 years the great Manor House, now known ironically as ‘Jack Straw’s Castle’, lies in ruins.

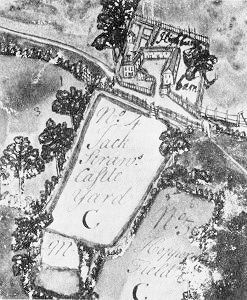

This black and white copy of a watercolour map of the area is from History of Highbury. Commissioned by landowner John Austen, drawn by John Johnson & dated 1718, it shows Church Path meeting present-day Highbury Grove. The Manor’s farm, Highbury Barn, sits on the upper side of the road facing the enormous moated site where the Manor House had been.

—————————————————————————————————-

Two remnants of the old moat become part of Victorian Highbury Barn’s Pleasure Gardens, as shown in the cover, right, of History of Highbury.

There was a fashion, in grand gardens of the time, called The Picturesque. ‘Ruins’, newly built, would be made to look weathered & ancient. Highbury Barn Pleasure Grounds had its own ready-made ruin from the sacking of its great Manor House.

Shops now face each other across Highbury Grange, where the Manor House & its farm stood centuries ago. Behind the shops, the Manor House land is covered with streets and houses. In 2010 the first Islington People’s Plaque was unveiled by former Member of Parliament Tony Benn and Islington Councillor Catherine West to mark the Peasants’ Revolt 1381. The plaque sits on the western wall of the Highbury Barn Tavern.

Tony Benn: ” ‘The Peasants Revolt’ was one of the early examples of a long series of public campaigns to secure freedom and democracy in Britain… a great moment in our long political history.”

Cllr Catherine West: ” It’s important that we acknowledge the events, people and organisations that have made their mark on Islington – whether hundreds of years ago or in more recent times. Although the revolt failed to achieve its stated aims, it succeeded in showing the nobles that the peasants were dissatisfied and that they were capable of wreaking havoc.”

www.islington.gov.uk/islington/history.heritage/…revoltplaque.dspx

————————————————————————————————————————

Sir Robert Hales is one of the ‘Tower Hill Martyrs’ who have died at this spot. A permanent scaffold was sited here for public decapitation. Important people, mainly royals, were executed nearby, within the grounds of the Tower.

The Execution Memorial is on the approximate spot of the scaffold and has a number of plaques listing the names and year of execution of many of the more well-known victims. The central plaque states that the memorial is:

“To commemorate the tragic history and in many cases the martyrdom of those who for the sake of their faith, country or ideals staked their lives and lost.

On this site more than 125 were put to death. The names of some of whom are recorded here.”

Around the edge of the memorial are four plaques listing the names of those executed.

Archbishop Sudbury’s ghost reportedly haunts both Canterbury Cathedral and St Gregory’s Church in Sudbury.

“The man whose cruel Poll Tax led to the Peasants’ Revolt and brought about his grisly death is said to appear at St Gregory’s Church in Sudbury: his disembodied footsteps pace the church he once founded. In Lantern, the periodical of the Lowestoft-based Borderline Science Investigation Group, there was a report in 1974 of bell-ringers in the 1920s hearing the footsteps as they practiced.

Born in 1316, Simon was killed in the revolt in June 1381 when he was dragged to Tower Hill and beheaded by a baying mob. His body was buried in Canterbury Cathedral but his head – after it was removed from London Bridge – was sent to St Gregory’s Church, where it remains and where it can be viewed by appointment.

It is fitting, therefore, that Archbishop Sudbury haunts both the Cathedral and the Suffolk church, perhaps his body visits his skull, which is kept in a glass case.

When the King regained control, the head of rebel Wat Tyler was placed on the same pole as Simon’s before the Archbishop’s head was secretly taken back to Sudbury. At Canterbury, where the cleric had been heavily involved with building work, his head was replaced with a cannon ball when his body was buried.

Interestingly, despite the fact that in death he was separated from his head, his ghost appears as intact at Canterbury where he has been seen as a pale, grey-clad figure in the tower which is named for him.

East Anglian Daily Times , Weird Norfolk, Stacia Briggs & Siofra Connor, 4th Feb 2021

Forensic artist Adrienne Barker of Dundee University used skeletal detail from the part-mummified skull of Archbishop Simon Sudbury, beheaded in the Peasants Revolt of 1381, to build up his facial features.

She then made a series of 3D bronze resin casts of his head. The project was carried out as part of Ms Barker’s MSc at the university’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification.

BBC News, 13 September 2011

Keith Sugden gives us, street by street, the direct route the protesters could have taken from St John’s Priory in Clerkenwell, which would have been still alight, to Highbury via what was known in the Middle Ages as Frog Lane. This important walk in our local history, now gone, would have been a wet, squidgy trek for all concerned.

Frog Lane was not destined to survive. In the Victorian era, developers building terraced housing over the area segmented the lane. An address on Canonbury Street, Willow Bridge Road, Nelson Terrace or Danbury Street would surely all prove more appealing to prospective buyers than muddy old Frog Lane… [See Living With London Wildlife/Frog page for more.]

The Hospitallers are St John’s Ambulance now, involved in humanitarian projects worldwide & most visible in the UK helping the runners at the annual London Marathon.

St John’s Gate, Clerkenwell (dating to 1504) survives the fire which consumes the rest of the Priory. Along with the Priory Church of St John, it now comprises the Museum of the Order of St John. It has a website,

The Village in History, Graham Nicholson and Jane Fawcett, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, Guild Publishing, The National Trust, 1988.

Highbury Manor, surrounded by villages, was part of the same medieval feudal system as the rest of the country.

The church played a major part in people’s lives: Parish churches conducted services and kept records of births, deaths and marriages. Each Parish was also responsible for the upkeep of the roads within its boundaries. This often amounted, when there were holes in the roads, to getting someone to fill the holes with stones.