The colour of London bricks may appear to be brown: brownish-yellow, brownish-black, sepia. But when the old bricks are cleaned, their original colours – dusty oranges, soft pinks and purples, mustard yellows – are revealed. The soot from over a century of coal fires and pollution that settled on their faces gave London bricks a grimy patina that obscured those true colours.

A look at today’s bricks, with their homogenized surfaces that are all one smooth colour, shows how things have changed. Any handmade element is gone. The perfection of the brickwork on new offices and estates could only have been achieved with mechanisation and robots. Planners can now organise huge quantities of bricks for their developments, and guarantee each one to be a smooth and perfect replica of its neighbours.

Many Highbury houses were built between the 1860s & the 1880s as plans for a sizable park in the area, famous for its fresh air & countryside, were being considered in Parliament. While the land was still open & unprotected, developers pressed on steadily, building new streets of terraced houses. Brickworks were in operation round the clock. Highbury’s rural landscape disappeared under new streets of brickbuilt terraced houses.

In his History of Highbury, Keith Sugden tells of the ‘ominous operations in nearby brickfields’ at this time – local brickworks churning out building materials.

Morgan, one of Islington’s Conservation Rangers, says an ancestor of hers had worked, as a child, at one of these local brickworks. He wore no protective clothing. He stood in a queue by the kiln with other workers, some of them children. The brickmaker, wearing heavy gloves, pushed a wooden paddle into the kiln & brought out a few hot, baked bricks. He turned, holding the paddle over the outstretched bare hands of the first person in the queue, & dropped the hot bricks into them.

That person then turned to the next worker & dropped the hot bricks into THEIR hands. And so on down the line. The brickworks offered local work a hundred and fifty years ago. Houses built in Highbury, as they were elsewhere in the country, involved child labour.

A few websites on brickmaking:

English Heritage Teacher’s Kit: www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/file/he/content/upload/10900.pdf

Isle of Wight Brickmaking History: http://www.iwhistory.org.uk/brickmaking/

(good diagrams, information on brickmaking methods)

This, then, is how our terraced houses were built – with bricks made from the clay of local brickfields, by labourers who included children. Bricks that are a baked version of clay as it came from the ground, colour variations and all. Rough & scorched in places, uneven and irregular.

This, then, is how our terraced houses were built – with bricks made from the clay of local brickfields, by labourers who included children. Bricks that are a baked version of clay as it came from the ground, colour variations and all. Rough & scorched in places, uneven and irregular.

Over the last few decades, with new people moving into Highbury, house renovation has meant that many of the old Victorian bricks are washed & brought back to life. Others are cast aside, tossed into skips & carted away. If they do not end up at a reclamation yard, they are pulverised into brick dust, losing all trace of their previous lives.

It seemed to me that these imperfect bricks were worth saving for our wildlife garden. Morgan’s ancestor might have handled them.

Years ago I saw a dry stone & brick wall at the Camley Street Nature Park. Many crevices had been left between the stones & bricks, meant as shelter for small creatures & places for plants to grow. I thought I would try something similar in our back garden, using the old Victorian bricks.

There are a number of maps on the web showing London Clay. This is one of them, redrawn. London Clay covers much more land than London alone, lying under part of Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Kent & Reading as well. It is closer to the surface in some places than in others.

There is orange-brown clay in our garden, claggy & difficult to dig. You hear London gardeners say they garden on London Clay.

Somewhere I read that London Clay is greenish blue-gray. There was some of that under our former path of rooftiles. A viscous substance, stickier than the orange-brown clay & a real struggle to prise from the trowel:

‘London Clay is not hospitable to most plants… ploughing it up where it lies so near to the surface as to be accessible to the plough is injurious to the surface soil and future crops. In Middlesex it is called ‘ploughing up poison’. Wikipedia Agriculture

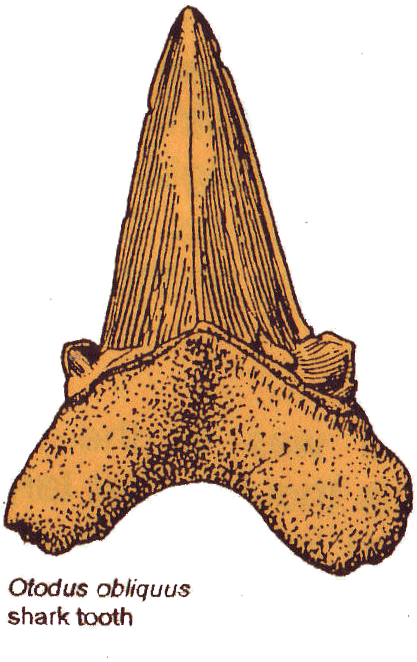

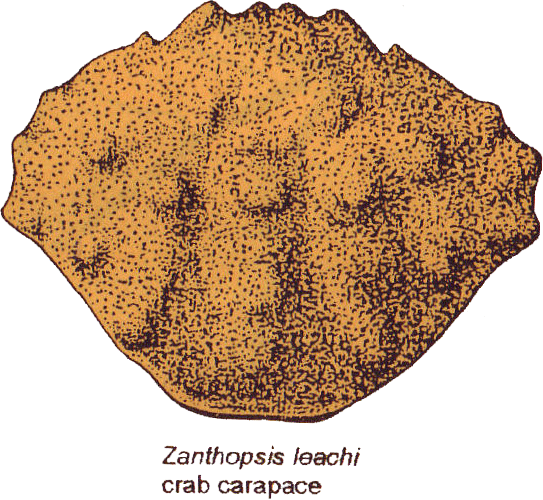

50 million years ago, in the Cretaceous Era, the southeast of the country was covered with a warm, tropical sea. Plants & animals living here included palms, magnolia, sharks & crocodiles. Fossils & remains of these life forms filtered down to the seabed & built up as chalks, clays, pebbles & sand.

On the London Clay of today, the London Boroughs of Islington & Haringey meet along The Parkland Walk. This Local Nature Reserve had been a railroad line. In the nineteenth century, two railway tunnels were dug into Highgate Hill, & spoil from the excavation spread out on fields. There they weathered, later made into bricks. Fossil collectors were allowed to help themselves.

In 1999 Palaeontologists from The Natural History Museum dug a trench along the old railway line in front of the tunnel. Drawings of fossil finds & a map of the local clay & brickworks were included in a leaflet produced by the Natural History Museum & the Haringey Parks Service, Geology of the Parkland Walk.

This was an enormous coordinated pulling down of the old Highbury Football Stadium by Sir Robert McAlpine’s crew, beginning in 2006. In this photograph, taken at dusk on a Nokia mobile phone, the orange tinge of the clay beneath what had been the football pitch can be seen. Were any fossils or seashells unearthed by the McAlpine diggers?

The much smaller dig into the garden behind our house found old bricks & plenty of clay, but nothing like what was happening across the road on the Highbury Stadium site.

In April 2011, six Victorian bricks from our garden went to an art gallery in Stoke Newington, Karin Janssen Project Space, where they were ART in an exhibition, ‘LOCAL‘. They supported a tray of stones, bones, broken crockery, snail shells, marbles and other items retrieved from the garden.

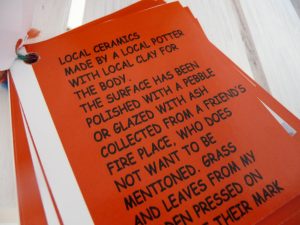

Another artwork in the exhibition was a selection of ceramics made of local Hackney clay by Tetrilia. This modern use of local clay was displayed in the Project Space near our bricks – Haringey clay fashioned into something useful by the Victorians.

Karin Janssen Project Space, 213 Well Street, London E9 6QU